Bi-Coastal Biology

From lichens growing on Maine granite to bacteria growing on the Mars rover, Picabo French ’19 spent her summer exploring biology with methods and purpose as diverse as her subjects.

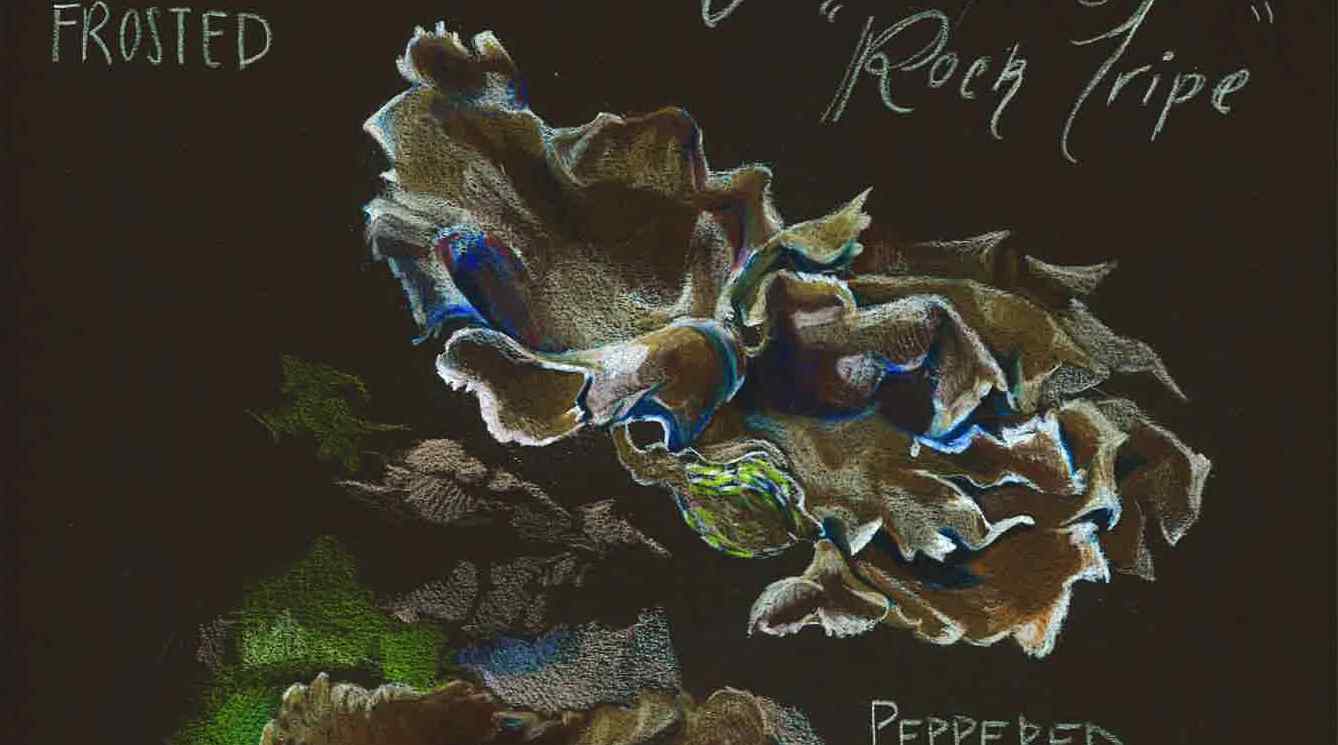

Picabo French's rendering of a lichen known as rock tripe

While working at JPL, Picabo French visited the Mission Control room in the Space

Flight Operations Facility.

While working at JPL, Picabo French visited the Mission Control room in the Space

Flight Operations Facility.

French, who started the summer in Acadia National Park in Maine documenting lichens—among the world’s oldest organisms—for a biological art project, ended it at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, examining bacteria on the Mars 2020 Project rover.

“I just wanted to get a wider breadth of different biological things this summer so I could tease out what I actually like,” says French, who hopes to become an oncologist, but who also loves medical illustration.

It all started, really, with Martin Connaughton, co-chair and associate professor of biology, Maine Summer Program leader, and lichen fanboy. French took an ecology class in which Connaughton’s enthusiasm for lichen sparked her own interest in the immensely old and diverse organisms that the uninitiated might recognize as just those grey-green splotches that grow on rocks and trees.

“They are amazing organisms,” says Connaughton. “They are pioneers in new, harsh habitats, good indicators of clean air (they don’t do well with pollution), and are masters of biochemistry. Some species produce their own sunscreen, produce compounds that prevent herbivores from eating them, and others that can convert UV light into light useable in photosynthesis. They can even produce their own antibiotics. Add to this their amazing variety and beauty, and you have something everyone should know about!”

French, a member of the Cater Society of Junior Fellows, wanted to participate in Connaughton’s Maine Summer Program, so she asked his advice about a project to fulfill a Cater grant for the trip.

“He said, ‘I really want someone to do something with lichen!’ So, I was like, well, I’ll do some more research on them and see what we can do. I found out all this stuff about the compounds they produce, but also just how beautiful they were.”

While Mount Desert Island, where Acadia is located, has hundreds of lichen species, French focused on about 20, which she examined both biologically and artistically. Using colored pencil, which allowed for more detail, she also thought carefully about the substrates on which the lichen grew and how to use canvas or paper to achieve that tonal quality of the larger environment.

“I really want to go into medical illustration, so I thought this would be a good way to prepare for that,” French says. “But I also just like drawing people in their environments, so I thought I would start out drawing something that looked just kind of stagnant but changes across different species and different environments.”

After several weeks hiking (carefully) over the ancient granite of Maine, French headed to California, where she had secured an internship through CalTech in the Planetary Protection Group of the Mars 2020 project at JPL. Connaughton had written her a recommendation after she found the internship through CalTech.

“I was like, oh, these people are part of biology, but they’re also at NASA, so that’s kind of weird,” French says. “I thought, I’ll never have the opportunity to do this again … I’ll learn something, so why not?”

The Planetary Protection Group works in microbiology to ensure that bacteria from Earth aren’t carried to Mars. Working primarily in the Flight Support Lab, French processed samples from the Mars 2020 rover hardware and assisted with sampling in clean rooms to ensure that bioburden requirements were being upheld.

“Even though they’re building it in clean rooms, there are still bacterial species that have evolved to deal with those extreme environments,” French says. “They don’t want to take bacteria to Mars, because that could have implications for the research they’re doing, since they’re trying to see if there is biological life. And, they don’t want to bring something that could harm Mars’s biosphere…So we would prepare media and samples and every 24 hours for 3 days you’d count which bacterial colonies grew, and then another member of the team would categorize genetically what was there or morphologically what was there.”

It’s a long way from Maine to Mars, but somehow, Picabo French made the trip in just one summer.

“I don’t know how that happened,” she says, “but I’m glad it did.”