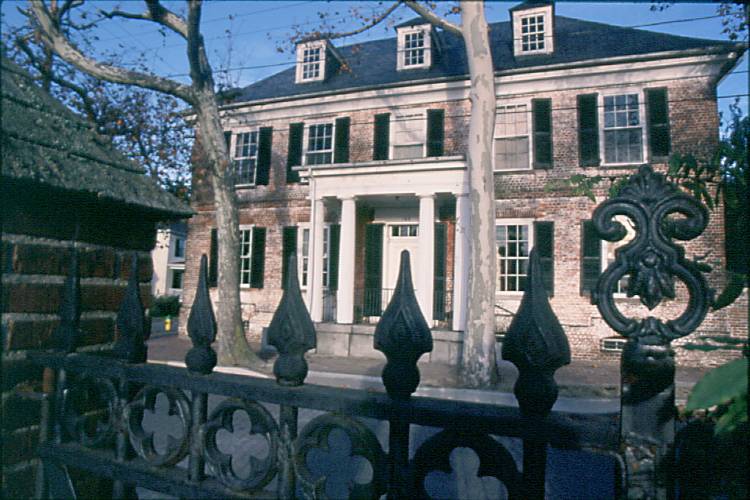

Hynson-Ringgold House

The 18th-century Hynson-Ringgold House has served as the home of Washington College’s presidents since 1950. It was also once home to generations of enslaved people. This account of its history is based on research conducted at the Starr Center in 2013 by Jamie Mansbridge, an international exchange student from Royal Holloway, University of London. Additional research was conducted in 2019 by students working on Chesapeake Heartland: An African American Humanities Project.

A House Served by the Enslaved

The Hynson-Ringgold House was built in 1743 as a private residence (and office) for Dr. William Murray, a physician who purchased the land in 1735 from local landowner Nathaniel Hynson. While the house changed ownership several times, records suggest that Dr. Murray was the only owner of the house prior to the Civil War who was not a slave owner. Between 1770 and 1863, approximately 25 enslaved people maintained and serviced the Hynson-Ringgold House.

In 1770, Thomas Ringgold V moved into the house after it was purchased by his father, Thomas Ringgold IV, a prominent merchant and slave trader who lived in the Custom House a block away. Owner of a plantation on Quaker Neck, the younger Ringgold made several additions to the structure, including servants’ quarters adjoining the rear of the house, which would have housed some of the 17 enslaved people he owned. Ringgold’s will lists at least three enslaved people—a “cook,” “boy in the house,” and “housewench”—who likely lived and worked in the Hynson-Ringgold House.

In the first two decades of the 1800s, the townhouse was again occupied by a plantation owner, Isaac Spencer, who ran a large farm outside of town. Records suggest that Spencer’s household included four enslaved African Americans and one free African American.

Between 1835 and 1853, the house was owned by James E. Barroll, a prominent lawyer in Chestertown and Washington College alumnus. Census records reveal that Barroll owned and lived with a number of enslaved people: in 1840, seven enslaved people ranging between 10 and 55 years of age were counted as occupants of the house, while in 1850, the house was served by three middle-aged men between 22 and 41 years of age and four enslaved women between 16 and 22.

The Free Black Community

Throughout these same decades, Chestertown’s first enclave of free African Americans sprang to life on lower Cannon Street, adjacent to the Hynson-Ringgold House. Henry Phillips, one of the earliest known Black landowners in Kent County, purchased a house at the corner of Queen and Cannon streets in 1796. In the 1820s, Thomas Cuff bought lot No. 5 just across the street from the Hynson-Ringgold House, subdividing the land and selling it to other African Americans, including Isaac Boyer and Levi Rogers, who along with his wife, Eliza, opened the Cape May Saloon. Cuff’s daughter, Maria Bracker, ran an ice cream shop out of her house at 104 Cannon Street. In 1828, Cuff and Boyer helped found Bethel AME church on the same block. Some of the free African Americans who lived on Cannon Street would have worked inside of the Hyson-Ringgold house for wages. Others would have had relatives toiling inside the house as enslaved servants.

College Trustee Defends Slavery—and Rights of Free Blacks

In the years between 1853 and 1862, the Hynson-Ringgold House was owned and occupied by U.S. Senator James Alfred Pearce. An early alumnus, longtime trustee, and part-time professor at Washington College, Pearce vigorously defended the right to own slaves while striving to maintain the Union at the outbreak of the Civil War. Pearce’s relationship with slavery was a complicated one: while he admitted that slavery was an “evil” that must eventually be eradicated, he also held slaves and opposed what he saw as extremist abolitionism that he believed to be unconstitutional. Pearce also served as defense attorney for his African American neighbor, Levi Rogers, who was prosecuted in 1858-59 for illegally leaving Maryland and returning, thus violating state laws restricting the travel of free African Americans. At the same time that he sought to defend the rights of his Black neighbor, Pearce owned and lived with nine enslaved people, some of whom Levi Rogers must have known personally, including a 7-year-old girl, a 4-year-old boy, and a 2-year-old toddler.

Pearce also employed a free “House Servant” named Moses Berry at the Hynson-Ringgold House, who in February 1864 enlisted in Company A of the 32nd United States Colored Infantry. Berry would fight admirably in the Battle of Honey Hill and be promoted to the rank of Corporal before being discharged due to a lung condition caused from “exposure in the line of duty.” After his service, Berry returned to the Hynson-Ringgold House to work for Pearce’s family as a gardener, and later moved to Washington, D.C., with his wife, Henrietta.

Hynson-Ringgold House Becomes Home of College Presidents

Through the efforts of Wilbur Ross Hubbard—entrepreneur, historic preservationist, and trustee of the College—the Hynson-Ringgold House was purchased in 1944, after years of physical deterioration, and gifted to Washington College to serve as the President’s official residence. Daniel Gibson, who served from 1950 to 1970, was the first college president to occupy the Hynson-Ringgold House.